Pinwill carvings at Crantock

The church of St Carantoc at Crantock is a minor masterpiece.1.

Introduction

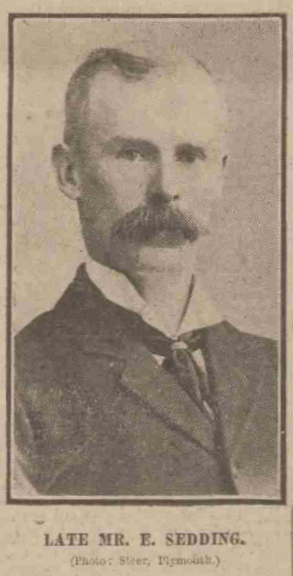

Figure 1. Edmund Harold Sedding. (Photo: Steer, Plymouth.)

From www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Image © Local World Limited/Trinity Mirror. Image created courtesy of THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD.

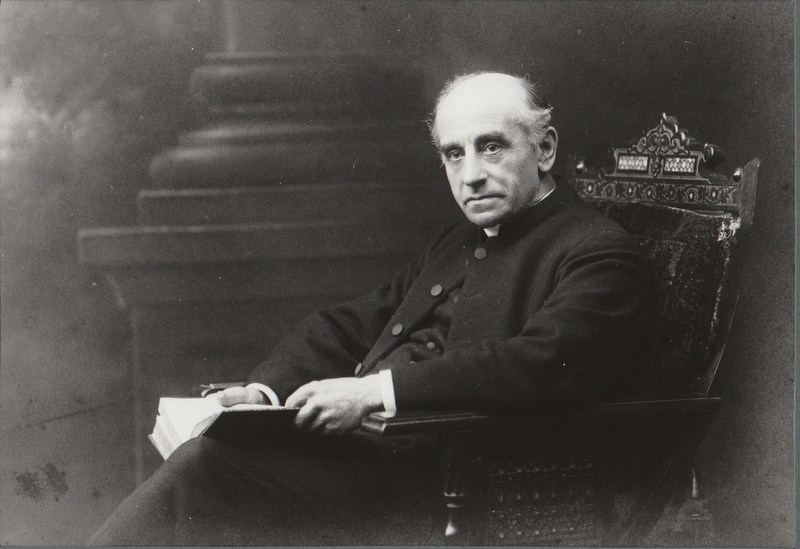

Figure 2. Father George Metford Parsons.

The restoration of the old Collegiate church of St Carantoc in the village of Crantock on Cornwall’s north coast by the architect Edmund H Sedding (Figure 1) and the incumbent Father George Metford Parsons (Figure 2) is rightly regarded today as one of the glories of Cornwall. Father George (as he was generally known) designed the integrated didactic scheme for the new stained glass windows throughout the church, but obviously most of the restoration was the responsibility of the architect.2

The quality of the new woodwork is usually given most prominence.

The principal beauty is its very rich High Church fittings, dating mainly from –. They include a splendid screen with coving, loft and rood, which incorporates a few medieval parts. There are fine parclose screens, rich sanctuary panelling, reredos, timber sedilia, and lavish stalls including four modern misericords. The pews have good carved ends in the late medieval manner. The largely renewed roofs have fine colouring above the rood and the sanctuary.3

Edmund Sedding entrusted the commission for the woodwork to the Plymouth firm of Rashleigh, Pinwill and Company. Revd Edmund Pinwill became rector of Ermington in Devon in , where the woodwork of the church was in dire need of restoration. Mrs Pinwill persuaded the woodcarvers to teach the craft to her daughters Mary, Ethel and Violet. As confidence in their skills developed, the three sisters decided to form their own business as professional carvers in restoring and creating woodwork under the name of Rashleigh, Pinwill and Company at Ermington. They opened a new workshop in Plymouth in . At the time of the restoration of Crantock (–), the offices and workshop of Rashleigh, Pinwill & Co. in Plymouth were at the same address as Sedding’s architectural practice, and remained so for many years.4

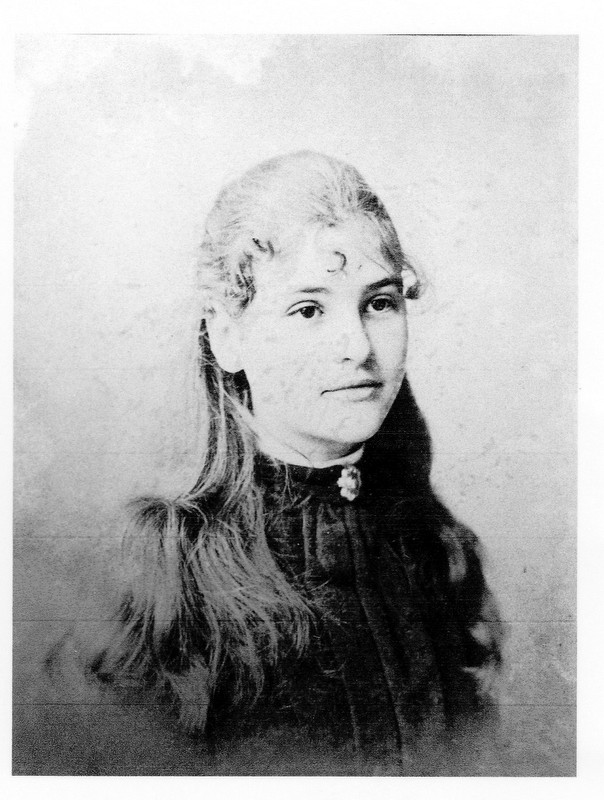

Figure 3. Violet Pinwill.

Copy of photograph held by Plymouth Archives, reference 255/6

Although the accepted local wisdom attributes to Violet the main responsibility for the Crantock carvings, this ignores the likely involvement of Mary and particularly Ethel in the work. In the absence of more detailed evidence, the term ‘Pinwill studio’ is used rather than the names of any one individual sister. The Faculties for the various stages of Crantock’s restoration specify ‘Rashleigh, Pinwill & Co’, except for that of (the nave bench ends) when the studio is simply listed as ‘Miss Pinwill’ (i.e., Violet).5 Mary’s marriage resulted in her leaving the business in 6 whilst Ethel remained at the Ermington workshop until her departure for Surrey in . During much of the Crantock restoration Violet managed the Plymouth base herself. She recruited and supervised additional carvers, as well as teaching the craft at Plymouth Technical College. Originally specialising in carvings of animals, flowers, fruits and vegetables, she moved on to the representation of religious figures. She died in aged 82 years, and her work is to be found in over 100 churches (Figure 3)

Rather than attempt to present a chronological account of the Pinwill carvings at St Carantoc, they have been grouped together under their form and function. This makes it easier to relate the carvings to the architectural and liturgical features of the restoration. The forms are grouped as (A) figurative carvings, (B) symbolic carvings and (C) decorative carvings.

(A) The figurative carvings

(ⅰ) The Sanctuary reredos

Figure 4. The reredos.

To a design by Sedding, the reredos (Figure 4) behind the High altar was one of the first fixtures of the church’s restoration to be installed.7 It contains four major and eight minor figures,8 and from the evidence of his scheme for the stained-glass windows,9 one must infer that Father George was closely involved with Sedding in their selection.

Figure 5. St Patrick.

Figure 6. St Piran.

The four major figures are St Peter (holding keys and book), St Patrick (with crozier and book, and a snake at his feet), St Piran (with millstone and crozier) and St Edward the Confessor (crowned with orb and sceptre). All the figures are related in some way to the early history of this church. Peter is patron of the Diocese of Exeter which in medieval times included all of Cornwall. Patrick was traditionally both a friend and patron of St Carantoc. Piran was also traditionally a friend of St Carantoc, and a typical major Cornish saint on this part of the north Cornish coast (Figures 5 and 6) Edward the Confessor’s reign was approximately when the original church became a Collegiate Foundation. The reason why the patron saint Carantoc himself is not included in the group is because he was to be the subject of all four nave windows in Father George’s scheme and is the subject of Nathaniel Hitch’s stand-alone statue opposite the main south door.

Figure 7. St Itha, representing ‘They which do hunger and thirst after righteousness’.

Figure 8. St George, representing ‘They that are persecuted for righteousness sake’.

The side niches are occupied by eight saints chosen to illustrate the Beatitudes, with the title of each in Latin inscribed on the base.10 Firstly, St Francis (with cross and showing the stigmata on his hands) represents ‘The poor in spirit’; below is St Anselm (holding book and stylus) representing ‘The meek’. Secondly, Mary Magdalene (carrying a container) representing ‘They that mourn’; below is St Itha (carrying a book and crook) representing ‘They which do hunger and thirst after righteousness’. Thirdly, St Bridget of Kildare (carrying a crozier and lamp) represents ‘The merciful’; below is St Agnes (with martyr’s palm and sword, accompanied by a lamb) representing ‘The pure in heart’. Lastly, St Ireneus (with crozier and palm) represents ‘The peacemaker’; below is St George the Martyr (with sword and shield, slaying dragon) representing ‘They that are persecuted for righteousness sake’ (Figures 7 and 8).

Several reasons can be inferred for the selection of these eight saints to illustrate the Beatitudes. They are accepted Anglo-Catholic saints selected to reflect Father George’s declared ritual status. Secondly, the inclusion of saints from the ‘Celtic’ fringes of Europe emphasises their significance in the history of Cornish Christianity. Lastly, the equal balance of male and female saints is remarkable for this time (pre-), especially as the female saints occupy the prominent central niches. Bearing in mind the lack of support from the parish that Father George experienced at the start of his incumbency, these figures can be viewed as a brave and robust statement of Anglo-Catholic beliefs in the face of threats from current non-Conformist and atheist sentiments.11

In conclusion, the Beatitude figures create a spatial context within the Chancel. Around the top of the parclose screens the fourteen Christian Virtues are inscribed, one for each of the misericord stalls. The Virtues link directly to the Beatitudes, and thus create a discrete reflective space highly appropriate to what was originally a medieval Collegiate chancel. The Virtues are (North) Caritas, Castitas, Probitas, Veritas, Sufficienta; (West) Sobrietas, Prudentia, Justitia, Virtus; (South) Obedentia, Religio, Reverentia, Adoratio, Pietas. One cannot help but feel that this was something dear to the hearts of both the architect and the priest, yet wonder how many of the pre- congregation and choir would have been literate enough to appreciate it!

(ⅱ) The Chancel Rood screen and Lectern

Figure 9. The rood screen.

The single most impressive carved feature of the restoration is Sedding’s rood screen of spanning both transepts and the nave, incorporating several uprights of the original medieval screen12 (Figure 9). It ‘is especially accomplished with large rood figures carried above a second tier of fine woodwork high in the chancel arch’.13 In this fine woodwork are fourteen apostles and evangelists carved by the Pinwill studio. Sadly, the lighting of the screen is so poor that identification of these figures is very difficult. From north to south the figures and their attributes are as follows:

- Matthias (halberd and book)

- Philip (cross)

- Bartholomew (flaying knife)

- Jude (spear)

- Andrew (cross)

- Luke (winged ox and book)

- Paul (sword)

- Peter (keys)

- Mark (winged lion and book)

- James the Great ((pilgrim’s staff and book)

- Thomas (builder’s square)

- Matthew (cross and book)

- James the Less (fuller’s staff and book)

- Simon (saw).

Figure 10. St Luke.

Like the carvings on the reredos, these figures face the congregation in the nave and are a statement to them of the importance of the leading figures in the New Testament narratives after the crucifixion, resurrection and ascension of Christ. The figures are so grouped that the major apostles (numbers 5–10) all directly face the nave (Figure 10). Spatially, this is significant as the adjacent south transept window in Father George’s didactic scheme shows the several witnesses to the Resurrection. It once again emphasises how the fixtures and fittings were conceived by Sedding and Father George to be read as an architectural and theological whole.

Figure 11. The rood group on top of the screen.

Incidentally, two saints are missing from the screen sequence. St John has of course a prominent position in the rood group on top of the screen14 (Figure 11) and St Barnabas is on the lectern below.

(ⅲ) St Michael

Figure 12. St Michael.

One further figurative carving made by the Pinwill studio is the fine St Michael in the corner of the Lady Chapel, again unfortunately badly lit (Figure 12). Originally this statue was at the north pier at the entrance to the sanctuary of the Lady Chapel, i.e., left of the altar, but was moved in the 1970s and replaced by the current statue of the B.V.M. Its original position marked the visual transition from the Marian narratives in the Lady Chapel windows and roof bosses to the Eucharistic sacramental area of the sanctuary and the vision of Christ in Glory in the chancel east window. St Michael’s role in the Last Judgement is one obvious link, but he has always had a special place in the medieval history of Crantock church both before and after the establishment of the Collegiate foundation.15

(B) The symbolic carvings on the nave bench ends

Figure 13. Bench ends.

The symbolic carvings on the nave bench ends have a theological significance equal to the figurative carvings. They were subject to a Faculty in in which the cost for the whole set was listed as £250 (Figure 13).

At first sight it is easy to think that the selection of the signs and symbols on the bench ends are purely random, based probably on medieval models. This would be entirely wrong and do a grave disservice to the amount of care and thought that Sedding and Father George put into the whole scheme of the church’s restoration. In fact, the scheme for the bench ends matches that of the stained-glass windows in its theological depth and complexity. The bench ends form a journey or sequence of nineteen stages in Christian belief and the Christian Church. This sequence commences at the first bench end on the north side of the nave; proceeds westwards down the nave; crosses to the ninth pew on the south side and then returns to the front south seat. The iconography and symbolism are summarised thus:-

The basic Christian Belief

- N1

- End of bookshelf for first seat:- The Holy Trinity. The inner links state (in Latin) ‘the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit IS GOD’: the outer links state ‘the Father, Son and Holy Spirit IS NOT Son, Holy Spirit or Father’.

The Gospel narrative, up to the Crucifixion

The rest of the north sequence launches the Gospel narrative, up to the Crucifixion. As it is a sequence, each bench end must be read right side (a) followed by left side (b).

- N2

-

- The Sacred Monogram IHS with inscription ‘Thou art the King of Glory, O Christ’.

- Lilies, the sacred flower of the Blessed Virgin, with the inscription ‘Hail Mary’.

- N3

-

- JR monogram—Jesus Rex, surmounted by a Royal Crown:

- MR monogram—Maria Regina, surmounted by a Royal Crown.

- N4

-

The Advent Antiphons:-

- ‘O Day of Spring’; ‘O King of Nations’; ‘O Emmanuel’; ‘O Virgin of Virgins.’

- ‘O Wisdom’; ‘O Lord of Hosts’; ‘O Root of Jesse’; ‘O Key of David.’

- N5

-

Figure 14. The Manger with a radiant star above and Crowns of the Magi surrounding a star.

- The Manger with a radiant star above:

- Crowns of the Magi surrounding a star (Figure 14).

- N6

-

- The Massacre of the Innocents, with the symbols of a dagger and palms, and inscription ‘Bethlehem’:

- The Flight to Egypt, with the symbols of the Sphinx and Pyramid, with the inscription ‘Egypt’.

- N7

-

- The Presentation at the Temple, with lamps and two doves in a basket:

- Early life at Nazareth, with carpenter’s tools and inscription ‘Nazareth’.

- N8

-

- Jesus’ Baptism, with IHC monogram, rays of glory, dove and star and inscription ‘This is my beloved son’:

- Wedding at Cana—the first miracle, with water pots and inscription ‘Cana’.

- N9

-

- ‘Palms’, with inscription ‘Hosanna’ and Crown of Thorns, INRI monogram.

- ‘Jerusalem’—Lamps and flowing water, with inscriptions ‘Light of the World’ and ‘Living Water’.

- N10

-

Figure 15. Symbols of the Passion, with pillar, cords and scourges and the Five Sacred Wounds of heart, hands and feet.

- Symbols of the Passion, with pillar, cords and scourges.

- The Five Sacred Wounds of heart, hands and feet (Figure 15).

Continuation of the Passion narrative, followed by the spread of the Gospel, and the Book of Revelation

Cross to the south pews for the continuation of the Passion narrative, followed by the spread of the Gospel, and the Book of Revelation:-

- S9

- S8

-

Figure 16. Pentecost, with dove descending and rays of light and the Spread of the Gospel, with IHC monogram surrounded by rays and book with inscription.

- Pentecost, with dove descending and rays of light.

- The Spread of the Gospel, with IHC monogram surrounded by rays with inscription on book ‘Their sound went into all the Earth’.18 (Figure 16).

- S7

- End of bookshelf:- Symbols of sword and crown of martyrdom, and inscription ‘ St Paul to the Gentiles’.19

- S6

- The Heavenly City.

The Church and the seven sacraments

After the Gospel and New Testament narratives, the sequence ends with The Church and the seven sacraments:-

- S5

-

Figure 17. The Church, with IHC monogram and Crown and Baptism, with Ark, dove and olive leaf.

- The Church, with IHC monogram and Crown.

- Baptism, with Ark, dove and olive leaf (Figure 17).

- S4

-

- Confirmation, with dove and inscription ‘Come Holy Spirit’.

- Holy Communion, with sacred host.

- S3

-

- Penance or Confession, with Bishop’s pastoral staff and crossed keys.

- Holy Orders, with stole, chalice and paten.

- S2

-

- Marriage, with ring surrounding a cross, a lover’s knot and clasped hands.

- Unction, with a vessel of Holy Oil, candle, stole and seven crosses: inscription ‘Our Help is in the name of the Lord’.23

- S1

- End of bookshelf for first seat:- Alpha and Omega, with the inscription ‘The Beginning and the Ending’.24 This is an apt ending to the sequence, mirroring the Holy Trinity opposite.

There is a strong connection between the schemes for the bench ends and the stained-glass windows within the architectural context of the nave and transepts. Only two of the stained-glass windows (Tower west—Nativity, and South Transept—witnesses to the Resurrection) portray pictorially the beginning and the end of the Gospel narrative. Eleven of the nineteen bench ends tell the Gospel narrative in symbolic imagery. One must conclude that both schemes were planned together and, as the windows scheme was formulated by Father George himself,25 then he also must have played a major part in drawing up the scheme for the bench ends along with Sedding. Father George’s involvement is supported by the fact that all seven sacraments are included, in accordance with his proclaimed Anglo-Catholic ritual status. One can only presume that Violet Pinwill must have been given a very detailed brief for the designs of the bench ends, and it would be fascinating to know more about the input of the studio into the finished designs.

We have already remarked how the positioning of the saints’ carvings on the rood screen relate to the congregation. The three great windows on the church’s cruciform shape (the two transepts and the tower) focus on the Fall, Nativity and Resurrection, with the rood Crucifixion part of this overarching narrative. Now we can see the bench ends completing this scheme with the Gospel narrative and the Church sacraments, forming a very satisfying theological and visual whole.

It is not too fanciful to imagine that Sedding and Father George planned all of this as a spiritual journey. Starting at the crossing facing the north transept Temptation and Fall window, and proceeding westwards, the viewer has the tower west Nativity window in sight whilst passing the symbols of Christ’s story. At the end of the north carved benches, the events of the Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension have been reached, but the viewer is also on the edge of the baptismal area of the nave containing the font and two nave windows in which baptism is a subtext.26 Turning eastwards the viewer is faced with the Crucifixion image of the rood screen, and whilst returning to the crossing all the other sacraments are unfolded in the south bench ends scheme. These carvings are therefore part of a fully integrated visual scheme of pictorial and symbolic iconography in wood and stained glass, all designed with a detailed didactic purpose at its heart.

(C) The decorative carvings

The final section examines the wide range of decorative carvings the Pinwill studio provided during the restoration. In many of these carvings, one feels that the imagination and artistic genius of the Pinwill sisters was allowed a freer rein by Sedding and Father George, and that the Pinwills were drawing on their earlier practical skills of using models from nature. Although their primary function was to enhance the aesthetic beauty of the chancel and Lady Chapel, the decorative carvings and inscriptions also provided an additional commentary on the liturgical aspects of these areas of the church (Figures 18 and 19).

(ⅰ) Sanctuary panelling

Figure 18. The sanctuary panelling.

Figure 19. The ogee arch over the door into the vestry.

The sanctuary panelling contains both a sedilia and a gilded aumbry as well as a fine crocketed ogee arch over the door into the vestry. Together they form a suitably dignified background to the richness of the Pinwill designs for the altar and stalls (Figures 18 and 19).

(ⅱ) High altar.

Figure 20. Palm leaves and grape fruit motifs on the front of the altar.

In artistic terms, there is a marked contrast between the Gothic-style reredos and the Arts & Crafts altar. The reredos, with its upper ornate open work and its elaborate gilded canopies, succeeds in drawing the eye to the sanctuary. The more restrained combination of palm leaves and grape fruit motifs on the front of the altar are of the highest artistic quality (Figure 20). Together with the un-gilded canopies on the altar front, these carvings are true Arts and Crafts products in the direct tradition of William Morris. This nature symbolism becomes the major artistic motif used by the Pinwills throughout the Chancel stalls.

(ⅲ) Chancel stalls.27

Figure 21. Poppy heads (pew finials) on the north choir stalls.

Figure 22. Bench ends in the north choir stalls.

On the north choir stalls, the pew finials or poppy heads are a whirling design of acanthus leaves around a scallop shell. The bench ends are a richly intricate design of fish and reeds or seaweed (Figures 21 and 22). The ends of the book shelves have heads of lilies above a spade motif (Christ the gardener) with ‘SC’ inscription, which could be ‘St Carantoc’ as the statue by Nathaniel Hitch in the nave has him holding his usual attribute, a spade. The back of each seat is inscribed alternately with a cross and heart, ‘M’ monogram and ‘IHS’ monogram, each separated with a traceried rose and trefoil design. The five stalls behind all have detailed misericords, most of which have motifs of various leaves and fruits.

Figure 23. Poppy heads (pew finials) on the south choir stalls.

Figure 24. Bench ends in the south choir stalls.

The south choir stalls poppy heads consist of the trunk of a vine with leaves and grapes, and this theme is continued into the bench ends in impressive detail (Figures 23 and 24). The ends of the book shelves have vine boughs above the Passion ladder and sponge motif. The back of each seat has alternately IHS monogram, cross and heart and JR monogram, each separated with a traceried rose and trefoil design. The five stalls behind have similar misericords to those on the other side of the choir.

What is remarkable about the choir stall carvings is the degree of intricate detail and variety in the designs combined with a virtuosic technique. All of this has symbolic iconography, particularly that of the Passion, woven into the overall design.

(ⅳ) Priest and Deacon stalls.

The most detailed and elaborate carving, however, is reserved for the two return stalls. They also afford the best view of the ends of the choir stalls immediately in front of them—a bonus for the clergy!

Figure 25. The poppy head of the priest’s stall: an oak canopy framing a dove.

Figure 26. The front of the priest’s stall.

The poppy head of the priest’s stall has an oak canopy framing a dove, the whole showing the most exquisite workmanship (Figure 25). The dove of the Holy Spirit is a recurrent theme of the windows in the Lady Chapel and in the ‘baptistry’ Carantoc windows in the south nave,28 where the dove also has a spray in its beak. The design of the rest of the bench end is clearly influenced by medieval models, but has a pleasing asymmetry that is decidedly modern. It includes two engraved shields, one of the sacred monogram and the other of a halberd (the attribute of Saint Matthew) with drops of blood. The front of the stall is a rich design of vine and oak with the monogram ‘JR’ in the traceried central panel (Figure 26). The two misericords show firstly a finely detailed Christ and the Lost Sheep with the inscription ‘Absolution’ and secondly an Agnus Dei with chalice and the inscription ‘Communion’.

Figure 27. The poppy head of the Deacon’s stall.

Figure 28. Detail of the poppy head of the Deacon’s stall, showing an an oak trunk with leaves and acorns.

The poppy head of the Deacon’s stall opposite is surmounted by an oak trunk with leaves and acorns. At the wall end is a rose and hip open design worthy of William Morris himself (Figures 27 and 28). One cannot help but think that Morris’ ‘Strawberry thief’ design was an inspiration to the carver for the birds feasting on berries and fruits on the front of the stall. The central panel is inscribed ‘Seanghus Mor’ referring to the ancient code of Irish Laws with which St Carantoc was traditionally involved, and which appears in the ‘baptistry’ St Carantoc north nave window.29 The first misericord depicts the Ark and rainbow with the inscription ‘Regeneration’, and the second The Holy Dove with the inscription ‘Confirmation’.

(ⅴ) Confessional Chairs in Chancel and Lady Chapel.

Figure 29. The confessional chair.

The quality of the carving on the confessional chair in the chancel is equal to any on the choir stalls. The symbolism of the sacrament of confession is complex and rare in an Anglican context, and another reminder of Father George’s ritual status (Figure 29). The intriguing inclusion of a chain and a serpent are both possibly emblems of sin. They have a richly foliate and fruit background leading to a strong diagonal of thorns symbolic of Christ’s crown of sacrifice. The strong vertical frond lines now enclose the Dove of the Holy Spirit with a spray in its beak, leading to a crown of redemption. The back of the chair has the symbols of the cross and crossed keys, and the inscription ‘In this place I will give peace, saith the Lord’.30

Figure 30. The two hinged flaps on the Lady Chapel side of the confessional.

On the Lady Chapel side of the confessional the two hinged flaps are inscribed ‘Mercy’ and ‘Grace: Peace’ (Figure 30). These flaps form a table beneath the crucifix on the grill, again emphasising the significance of the sacrament of confession in Father George’s High Anglicanism. It is worth noting how each inscription is framed by yet more beautifully presented Morrisian foliage and fruit motifs.

(ⅵ) Chancel roof bosses.

Figure 31. A roof boss in the chancel.

Figure 32. A roof boss in the chancel.

Before leaving the chancel, one must acknowledge the richly decorated barrel roof with its roof bosses. These were repainted after fire damage in the 1980s, but the Faculty for does not specify whether Sedding’s original colour scheme was followed31 (Figures 31 and 32). Like so many of the Pinwill carvings in the chancel, they fulfil a decorative function that follows medieval precedents, but also there are many symbolic references. Amongst the motifs on the bosses are roses, oak leaves, acorns, vines and grapes. On the string course are two praying angels facing the altar and a series of shields. One of these has seven stars, and above the altar are the sun and the moon (Figures 33 and 34).

Figure 33. A praying angel on the string course in the chancel.

Figure 34. A shield on the string course in the chancel.

(ⅶ) Lady Chapel roof bosses and furnishings.

Figure 35. A roof boss in the Lady Chapel, depicting the Annunciation.

Figure 36. A roof boss in the Lady Chapel, depicting the Throne of Solomon.

The roof bosses in the Lady Chapel, however, have a far more obvious didactic function, and again, as with the window scheme, one must conclude that Father George was the prime mover in the selection of the subjects: ‘the bosses in the roof above are symbolical of the Incarnation and the Blessed Virgin Mary’.32 The iconography of the bosses includes The Angel in the burning bush, the Ark of the Covenant and the Throne of Solomon, and the sacred monograms ‘BVM’ and ‘MDG’ (Figures 35 and 36). There is a direct connection with the subjects in the sequence of Marian windows on the south wall of the Lady Chapel.33 Just as with the nave bench ends and the west and south transept windows, one marvels at the level of complexity and theological argument involved in the Lady Chapel using different visual media within a defined architectural and liturgical space. The intricacies of Sedding’s and Father George’s schemes must have been influenced by Bishop Benson’s schemes with John Loughborough Pearson and Canon Arthur James Mason in the new Truro cathedral that was nearing completion at the same time as the St Carantoc restoration.34.

Figure 37. The altar rails.

Figure 38. The alabaster altar front.

The Pinwill studio was also responsible for the delicate and complex altar rails.35 Each is in three panels, the smaller outer ones with a traceried pattern that reflects medieval bench end patterns. The larger central panel is dominated by a crown of thorns to great artistic effect. The inscription that spans both rails is ‘Hail True Body born of the Virgin Mary; Truly suffered, sacrificed on the Cross for Man’36 (Figures 37 and 38). Some of the design features in the altar rails, such as the quatrefoils, are also included in the alabaster altar front in this chapel. There is no evidence that the Pinwill studio was responsible for the altar,37 but the common features suggest that the basic designs for both commissions were made by Sedding in consultation with Father George.

(ⅷ) Pulpit and lectern.

Figure 39. The pulpit.

Figure 40. A foliate Arts & Crafts band on the side of the pulpit.

The final group of carvings are the fixtures in the Transepts and Crossing. The pulpit is a traditional octagonal shape with heavily carved uprights and eight legs,38 with each side containing an open panel decorated with a foliate Arts & Crafts band. These bands mirror many of the chancel carvings alternating roses, vines with grapes and oak with acorns (Figures 39 and 40).

The lectern39 has the figure of St Barnabas on the front. He is depicted holding a staff relating to his journeys, many with St Paul, and holding a book, which is usually attributed to St Mark’s gospel.

(ⅸ) Transepts.

Figure 41. The altar frontal chest in the south transept, showing some Symbols of the Passion.

The south transept contains the altar frontal chest with more symbols of the Passion, namely the scourges, a ladder, dice and spear, mirroring the nave bench ends (Figure 41). The strong room in the north transept is cased with panelled and carved oak made by the Pinwills and designed by Messrs Sedding and Wheatley. The cupboard door contains a round seal with the inscription ‘The seal of the Dean of St Crantock’. This is set within a Romanesque arch, whilst there is a smaller Romanesque arch below. Both are examples of fine workmanship, and were found by Father George in the village in and incorporated within the outer panel.40

Figure 42. Medieval-style door in the pillar within the choir vestry.

In the pillar within the choir vestry, there is a fine medieval-style door that almost certainly was produced by the Pinwill studio, as the upper and lower panels have their characteristic oak and vine motifs (Figure 42). The central panel of the door, however, is the Jacobean front panel from the old pulpit before the restoration.

A footnote on the numerous inscriptions throughout the Pinwill carvings and the Tute stained-glass windows at Crantock is that they are all resolutely in Latin. There is no little irony that their intention was to be a didactic teaching tool, but in a language that was unintelligible to most of the congregation!41

Conclusion: wider context.

All the repairs or replacement of furniture are conceived in the style or the spirit of the (medieval) fragments that have been preserved.42

No greater compliment to the work of the Pinwill studio at Crantock could be paid than this comment. Working alongside the meticulously historical professionalism of Edmund H Sedding and the Anglo-Catholic vision of Father George, we have seen how they produced a varied and artistically inspired body of work to grace the restoration of this old Collegiate church. We have also seen how the various schemes of carvings in different parts of the church combined with that of the stained-glass windows to produce the most comprehensive theological and artistic whole that is unmatched in Cornwall or indeed in much of the South West.

Perhaps this is the moment to place the Pinwills within a wider artistic context of the final decades before . The principles of Ruskin and Morris were the basis for the emerging Arts & Crafts movement from onwards. In this context, wood carving, like stained glass painting, was deemed to be a respectable occupation for young ladies at that time, and the most adventurous students did indeed set up their own businesses. There is a very strong gender context to the Pinwills’ work at Crantock in that it was part of an art form led by women as entrepreneurs and artists, even before . The work of the Pinwill sisters therefore

sits well with the ethos of the Arts and Crafts Movement in which women were well represented. Whether the sisters were directly influenced or saw themselves in that mould is not clear, but today there is every reason to place them alongside the likes of Sara Losh, Edith Dawson, Mary Lowndes and the many other under-recognised women artists of that era.43

When the church was reopened in , a correspondent for

The Church Times described the effect as if the rarest art and genius have combined

to make this House of God as fair as any in the land

.44

Perhaps the final words should be those of the inspired architect and patron of the Pinwill studio,

EH Sedding:

The old collegiate church once again possesses its stalls, screens, coloured glass, and carved imagery, and is therefore redeemed and put right again in the sight of those who reverence God’s sanctuary. 45

For all concerned, it was indeed a labour of love.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the help and support given by Dr Helen Wilson in the production of this article. All opinions are those of the authors.

References

- Peter Beacham, The Victorian, Victorian Society Journal, .

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith, A Victorian Vision re-discovered: the stained-glass windows of St Carantoc, Cornwall, Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, , pp 25–42. A newer version is also available.

- Paul Jeffery, The Collegiate Churches of England and Wales (London, ) p 117.

- Helen Wilson (1), The emergence of the Pinwill Sisters, Devon Buildings Group Newsletter No 34, 2016. Mary left in 1900 and Ethel by 1908.

- Canon Michael Warner, A gazetteer of works on Cornish Anglican Churches, – (database items available via Diocesan House, Truro).

- Helen Wilson (1) op. cit.

- faculty.

- Helen Wilson (2), The Pinwill Woodcarving catalogue, section on Crantock, Cornwall.

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith op. cit.

- Throughout the article, all Latin inscriptions are translated into English.

- Michael G Swift, A Victorian vision fulfilled—the stained glass of Truro Cathedral (), Introduction and Conclusion.

- Helen Wilson (2) op. cit.

- P Beacham and N Pevsner, Buildings of England—Cornwall, p 166 (Yale, ).

- The rood group of the crucifixion, the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John, was not carved by the Pinwill studio, but was made at Oberammergau.

- St Michael has always been regarded as one of the three patron saints of Cornwall. From the Norman Conquest, the Collegiate church at Crantock was in the possession of the Mortain family who carried a banner of St Michael into battle. St Michael therefore has both secular and ecclesiastic significance in the history of Crantock church.

- and : and . and .

- .

- : : .

- .

- .

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith op. cit.

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith op. cit. Nave north 2 and south 2 windows.

- All the chancel stalls were inserted for the consecration in .

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith op. cit. Lady Chapel south and Nave south 2 windows.

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith op. cit. Nave north 2 window.

- .

- Canon Michael Warner, op. cit..

- Church of St Crantock—carvings and inscriptions p 19. A hand-bound, typewritten and hand-drawn booklet unsigned and undated.

- Michael G Swift and Jeni Stewart-Smith op. cit. Lady Chapel south windows 2 and 1.

- Michael G Swift, op. cit., Chapters 2 and 3.

- Inserted for the consecration in .

- From the hymn ‘Hail True Body born of Mary.’

- The altar frontal was possibly the work of Nathaniel Hitch who was responsible for the nave St Carantoc statue. This, together with the Lady Chapel altar and altar rails were all part of the restoration.

- Helen Wilson (2) op. cit.

- Helen Wilson (2) op. cit. This lectern was not in place at the consecration service in .

- Original Church inventory, : strongroom planned by Father George.

- Michael G Swift, op. cit., Chapter 13. It was in , in the middle of the Crantock restoration, that Truro cathedral took the decision to change from Latin to English inscriptions!

- Church of St Crantock—carvings and inscriptions p 18.

- Helen Wilson (1) op. cit.

- Helen Wilson (2) op. cit.

- Edmund H Sedding, Norman Architecture in Cornwall, p 71. London, .