Stained glass war memorials in Cornwall

This article is based on a presentation with the title

Pro Patria Mori—Cornish stained glass images of loss and remembrance

given in Truro on .

Stained glass memorial windows

The practice of inserting stained glass memorial windows in churches did not become popular until the early s. James Markland’s advocacy1 in that such windows were a more suitable alternative to stone monuments was part of a broader architectural response to the publications of the Oxford movement and the Tractarians. The Diocese of Exeter, which then included Cornwall, was one of the first to establish a Diocesan Architectural Society, and enthusiastically followed Markland’s advice.

Obituary windows of richly painted glass serve every purpose which the pious affection of surviving relatives can desire, whilst heightening the general effect of the church’s interior by spreading a warm religious glow. It is pleasant to find this method of commemoration is beginning to be widely adopted: there are some instances in our own Diocese.2

Beati mortui qui moriuntur in Domino (Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord) ().

Figure 1. Memorial window at Lostwithiel.

The earliest memorial windows in Cornwall were inserted at Lostwithiel, and , in (Figure 1) and the next two decades saw their insertion throughout Cornish Anglican churches.4

The purpose of this article is to concentrate on the windows in Cornish churches dedicated to those who had died in war, and to establish that such windows are significantly different from the majority of normal memorial windows.

War stained glass windows are also significantly different from public war memorials. From onwards, secular war memorial monuments were usually sited in public external spaces and were for communal memory. They usually depict either servicemen in uniform or allegorical figures. By contrast, stained glass war memorial windows are almost entirely sited in sacred internal spaces, the majority are for a single individual, and they show a much wider range of both sacred and secular iconography.

There are fifty-one stained glass war memorials in Cornish Anglican churches. A breakdown of the insertion dates for these windows shows the following pattern:-

| Pre- | (The British Empire wars) | 9 | |

| – | (The Great War) | 35 | of which 12 were inserted before the end of hostilities. |

| Post- | (The Second World War) | 7 |

Through using this fairly small sample, this article examines the ways in which the icography of Cornish windows shows changing attitudes towards the remembrance of those who have fallen in war, and so reveals shifts in cultural values in society. It would be interesting to see whether these findings are reflected elsewhere in the country. It must be remembered that the choice of subject-matter of such windows was a personal decision by grieving families or communities: the modern viewer is challenged to interpret the resulting iconography in that context.

Memorial windows of the British Empire wars pre-

Figure 2. General Gordon in the memorial to Queen Victoria (n32) in the north nave aisle of Truro Cathedral. In his left hand he holds a copy of the bible.

The earliest Cornish war memorial windows cover the wars waged throughout the British Empire in India, Egypt and South Africa. In , it was decided that the suitable nineteenth century icons to accompany Queen Victoria in her memorial window, , at Truro Cathedral were the Christian poet Tennyson and the Christian soldier General Gordon (Figure 2). Although only nine windows were inserted in this period, their iconography shows many of the themes and subjects that were later used to commemorate the fallen of the Great War.

Sam C V .

Then said David to the Philistine, Thou comest to me with a sword, and with a spear, and with a shield: but I come to thee in the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, whom thou hast defied ().

Figure 3. Memorial at Kilkhampton to Capt William Frederick Thynne.

Kilkhampton, : Capt William Frederick Thynne was killed at Lucknow in , and a Clayton and Bell memorial window of portrays nine Old Testament events of conflict, focusing on the actions of Joshua, Gideon and David (Figure 3). In sum, these images portray the pursuit of a just war against an enemy.

Figure 4.

Memorial to Lt Teignmouth Melvill, VC, at St Winnow.

The central light shows the Resurrection. The angel in the left-hand light

holds a scroll on which is written O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?

()

and the scroll held by the angel in the right-hand light reads

But thanks be to God, which giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ

().

In the tracery above are, on the left,

St Stephen, the first Christian martyr and, on the right, St Alban, the first

British martyr.

At St Winnow, , a memorial window to Lt Teignmouth Melvill records the award of the Victoria Cross for his actions after the battle of Isandlana in . The main subject of this window is the Resurrection, but the tracery contains the images of the martyrs Stephen and Alban, implying a Christian subtext to his death (Figure 4).

Figure 5. Memorial to those who died in the Egyptian campaign of – at St Petroc, Bodmin. The figures are, from left to right, Saints Michael, Petroc, Piran and Longinus.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

St Petroc, Bodmin contains a number of windows commemorating the memory of members of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry over many campaigns. The window for the Egyptian campaign of – introduces new themes to military memorials. St Michael defeating Satan signifies Good triumphing over Evil, whilst Longinus at the foot of the Cross marks the conversion of a soldier to Christianity. The other two images are of Saints Piran and Petroc, one of the earliest uses in stained glass of the Cornish saints (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Memorial at St Petroc, Bodmin, to those who died in the Boer War. The figures are, from left to right, Saints Martin, Maurice, Gerron and Longinus.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

Figure 7. Lower panel of the window shown in Figure 6. A cavalry battalion, supported by infantry, is shown overwhelming a defeated and retreating army.

Two Cornish windows commemorate the Boer War. At St Petroc, Bodmin, the regimental memorial window, , for the Boer War is the most ambiguous of all Cornish war memorial windows. The main lights show Saints Martin, Maurice, Gerron and Longinus (Figure 6). All were soldiers, and the middle two, in renouncing warfare, became martyrs for their faith. Both Martin and Longinus turned to peace when they accepted the Christian message. This is in complete contrast to the lower panels which depict one of the most graphic portrayals of an act of war in Cornish windows. A cavalry battalion, supported by infantry, is shown overwhelming a defeated and retreating army (Figure 7): a very powerful imperialistic image. It is difficult to reconcile this with the pacifist sentiments in the main section of the window.

The second Boer War window is at

Laneast,

,

where the Blessed Virgin Mary with child is shown flanked by St George and the patronal saint Sidwell.

The dedication of this window is for the safe return from the South African War

of three members of the Lethbridge family.

A similar dedication beneath the Tinworth panel

in Truro Cathedral marks the safe return of two sons of the High Sheriff of Berkshire.

Within the space of a dozen years, such sentiments would never again occur after

the scale of the casualties of the Great War. Indeed, one wonders at the appropriateness of such ‘memorials’

when at the other end of the cathedral, Frank Loughborough Pearson’s impressive

Boer War memorial records the names of nearly three hundred Cornish servicemen who died

in that war and who have no individual memorials (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Memorial in Truro Cathedral to Cornish servicemen who died in the Boer War. From a glass negative in the custody of the Royal Cornwall Museum, reference no. TEcin.2, and used with the permission of the RCM. The original photograph was probably taken by Arthur Philp.

This small sample of windows thus establishes some common iconographic themes that were used in pre- war memorial windows. The images used for both individual or group memorials encompass themes of the resurrection and judgement, of just wars and the triumph of good over evil, of the national saint and those saints associated with soldiering, and of patronal and Cornish saints. We shall now see how such themes were used in memorials to the fallen of the Great War, and some of the newer images that appeared from that conflict.

The Great War of –

Probably the most famous of the Cornish dead of the Great War was the Hon T (Tommy) CR Agar-Robartes. His memorial in Truro Cathedral is a focus during the annual service of remembrance, and there are two memorial windows to him in the estate church at Lanhydrock. Both were installed in . shows the women at the empty tomb with two guardian angels: the texts assert the certainty of resurrection and a life after death. is more complex. Three archangels are portrayed, Gabriel, Michael and Raphael. The three predellas below show the appearance of angels to Daniel, Joshua and Elijah, so establishing a typological relationship. Both windows place angels central to the act of memorial.

Traditional images

To the greater honour of God & in loving memory of Lieutenant Arthur Donald Sowell 7th Battalion D.C.L.I. who fell in action in the Battle of the Somme aged 21

Figure 9. Kea, All Hallows, . On the left is St Michael and on the right is St George. At the feet of each there is a vanquished dragon.

A selection of the traditional images used to commemorate fallen soldiers includes Saints Michael and George in Kea, All Hallows, (Figure 9), and Saints Michael and George with the Archangel Raphael (usually associated with healing) at Rame, . The Sawle memorial at Porthpean comprises four separate windows showing King David (), St Michael (), St George () and the angel of Smyrna (). St Michael, St George and the archangel Gabriel are the subjects of the window in memory of L Cpl Arthur Trestain Williams at Lanreath, , whilst his name is included on the memorial elsewhere in the nave to the eighty men of Lanreath who were killed (the officers are marked out in red lettering).

Personalised images

To the glory of God and in loving memory of Sec. Lieut J.P. Gilbert 1st Hampshires who was killed in action in France on aged 31 years. A man greatly beloved. May he rest in peace.

Figure 10.

Memorial in St Paul, Chacewater. The angel holds a tablet

on which is written Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his

life for his friends

().

The use of photographic images for the painting of the faces of the dead commemorated in stained glass windows began as early as , but became commonplace for the fallen of the Great War. At Chacewater, , 2Lt Joseph Gilbert is shown in uniform at the foot of the cross (Figure 10), whilst at Treverbyn, , the kneeling 2Lt Charles Gill is at prayer at the foot of the Cross.

Ye have seen [what I did unto the Egyptians, and] how I bare you on eagles’ wings and brought you unto myself ()

In memory of

Lieut. Ronald Baynton Picken, R.A.F.

who was killed in an air fight off Albania. , aged 20.

Also of Mabel Marion Picken his mother

who died five months later, aged 50.

The window above was erected by

the bereaved husband and father, Henry Moore Picken.(Inscription on a plaque near the window)

Figure 11. Memorial in St Martin by Looe to Lt Robert Picken, RAF.

Often the soldier is also portrayed in medieval armour, as at St Martin by Looe, , where the Picken memorial shows Christ presenting a crown to the armoured soldier, guarded by Longinus and comforted by his mother. Both soldier and mother are shown by photographic likenesses (Figure 11). There is a similar personalised image of a medieval knight at Saltash, , in the Pym memorial (Figure 12).

To the Glory of God and in dear Memory of John Scarlett Pym DCM Scout Sergeant Royal Canadian Dragoons afterwards Second Lieutenant The Queen’s Regiment Killed in Action on the River Somme only Son of Flora and Walter HJ Pym Payr Captain Royal Navy.

Figure 12.

Memorial in St Nicholas and St Faith, Saltash.

The banners at the top of the outer lights read Be thou faithful unto death

and I will give thee the Crown of Life

().

Collective memorials

The majority of Great War memorial windows are for individuals (almost always officers),

but some do commemorate all the servicemen from the parish who were killed.

At Lelant,

,

Saint George slaying the dragon is the main image commemorating

the Lelant men

, and besides the Royal coat of arms there are also the arms of

the Duchy of Cornwall and the Diocese of Truro.

To the glorious memory of the men from this parish who fell in the war – R.I.P.

Figure 13. Memorial in St Gennys. The scene shown is Noli me tangere (Touch me not) () with Mary Magdalene before Christ in the garden after the Resurrection.

At St Gennys,

,

the men from this parish

are remembered by the image of Noli me tangere

with Mary Magdalene before Christ in the garden after the Resurrection (Figure 13).

Requiescant in pace (May they rest in peace).

| J Barnes | C Osborne |

| J Chenhalls | W Prowse |

| JE Davey | G Reseigh |

| P Davey | F Roberts |

| J Eadie | A Rowe |

| H Eddy | HW Rowe |

| F Friggens | WF Rowe |

| WJ Harvey | J Rowe |

| WS Harvey | WT Semmens |

| J Hocking | WP Stevens |

| R Hocking | W Stone |

| S Jelbert | FH Thomas |

| J Leggo | J Thomas |

| W Littlejohns | WO Thomas |

| HG Maddern | H Trembath |

| W Mitchell | R Trewern |

| T Murley | W Trewern |

| J Oates | J Wallis |

| C Olds | WJ Williams |

Pro Rege et Patria (For King and Country) –.

Figure 14. Memorial at St Just in Penwith to all the members of the parish who died in the Great War.

A remarkable collective window is at St Just in Penwith, , where 38 members of the parish are listed, with the badges of the Cornish regiments. The main image is of the Crucifixion, but the soldier at the foot of the Cross is an ordinary British Tommy (Figure 14).

Figure 15. Memorial in St Petroc, Bodmin, showing a wounded soldier with his rifle and helmet, kneeling at the foot of the Cross.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

The only other window where the ordinary soldier is portrayed is in the – regimental window, , at Bodmin (Figure 15). The wounded Tommy with his rifle kneels at the foot of the Cross, which is flanked by images of Saints Guron and Dennis. The predellas below show the main religious buildings in four areas of battle—Ypres, Merville, Arras and Albert.

Finally, there are three Great War memorial windows in Cornwall that deserve closer attention. Each in its own way presents a fresh approach to the sense of loss, grief and remembrance compared to the windows already listed.

The Bolitho memorial at Paul

In honour of William Torquill Macleod Bolitho.

Lieut 19th Hussars. Born . Fell in action at Chateau Hooge Second Battle of Ypres.

And you will speed us onward with a cheer

And wave beyond the stars that all is well

(the last two lines of the the poem

‘Julian Grenfell’ by Maurice Baring

(–))

Figure 16. The Bolitho memorial in Paul parish church in memory of Lt William Torquill Macleod Bolitho, portrayed as Sir Galahad.

Photograph copyright © Peter Hildebrand

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

The first is the chancel east Bolitho memorial at Paul parish church, designed by Robert Anning Bell in . In terms of design, technology and artistic ambition this remarkable window is one of the most significant Arts and Crafts windows in the Southwest, but for present purposes our attention is concentrated on the iconography. The tracery consists of charming young angels playing musical instruments—a signature Bell motif signifying innocence. The main subjects in the five lights below contain the most complex imagery. The panels in the three main lights show the soldier as Sir Galahad, leading a horse, and surrounded by angels (again mostly young) (Figure 16). The photographic likeness of the knight identifies the dedicatee as Lt William Torquill Macleod Bolitho, who died in the second battle of Ypres, . The outer lights contain six panels of intertwined motifs surrounding young angels again, with indicators of Bolitho’s military career (Ypres, Hooge, Cornish arms, military insignia, etc.). Below these panels is a coastal seascape, extended across all five lights, which has been read as the view of the western Lizard peninsular as viewed from the churchyard of Paul church. If all this were not enough, the heads of the five lights contain the window’s unique feature, namely a detailed view of the battlefield on which Bolitho lost his life. The scene includes roads, buildings and the lines of the opposing armies (Figure 17).

German Trenches. British Trenches

Figure 17. Detail from the top of one light of the Bolitho memorial in Paul parish church.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

Such a complex window was the result of the closest cooperation between the donors (the Bolitho family) and the artist. A plaque indicates that the window was also dedicated to William Bolitho’s uncle Lt Torquill John Pollard Ross Macleod, who died at sea in , and his cousin Mid Torquil Harry Lionel Macleod who, with five named others from the parish of Paul, died in the Dardanelles in . Despite this, the whole impact of the window is as an expression of loss and grief for one single soldier. This raises questions about the context of such a memorial window, sited as it is above the main altar in the chancel and the focal point for the whole church. Such expressions obviously caused concern as the war progressed and the demand to insert war memorial windows increased, and this response was made:

I would therefore like you to discourage the introduction into your church of any individual war tablets and by doing so you may sometimes prevent (inter alia) the rich man’s son having his name prominent whilst that of the poor man’s son is left in obscurity.21

RM Paul, Chancellor to the Diocese, .

One cannot but conclude that the Bolitho window at Paul was one that caused the Chancellor to make such a strong comment.

Launceston College

Pro Patria

In honoured memory of the boys of this school who fell in the Great War –

Figure 18. Memorial in the schoolroom of Launceston College to former pupils who died in the Great War.

The second remarkable and particularly poignant Great War memorial window was inserted in the

schoolroom

of Launceston College.

The main central light under the sign Pro Patria

lists the names of 29 former pupils who fell in the Great War. On either side are the

images of St George (Patron saint of England and of soldiers

) and St Nicholas

(Patron saint of sailors and of schoolboys

). In the panels above are sadly faded allegorical

representations of Art, Literature, Music and Mathematics (Figure 18).

This sad and affecting window is a powerful expression

of the sense of loss of the potential of those that did not survive. The same can be said for the

memorial window

in what was the old Truro Cathedral choir school where,

beneath images of Gabriel and St Michael, are listed the names of 19 ex-pupils

who were killed in the Great War.

St Stephen by Launceston

To the fallen

Figure 19. Memorial in St Stephen-by-Launceston.

The final window in this section on the Great War is at

St Stephen-by-Launceston,

.

The tracery is full of music-playing angels and texts of various virtues such as

Justice

, Mercy

, Love

and Joy

. This sets the tone for the five main lights.

The central one is a standard representation of St Michael, but the other four successively portray

War, Devastation, Peace and Plenty (Figure 19). This is a rare example of a war memorial window

(the dedication is simply To the fallen

) which looks beyond the harrowing aspects

of the recent conflict towards the prospect of a better future, introducing a reflective element

into Great War memorial stained glass windows that is quite unique in Cornwall.

Memorial windows of the Second World War

–

| Harry Lightfoot | Fritz Parsons |

| Arthur Hayes | Richard S Ted Phillips |

| Alfred Hill | T Jasper W Rowland |

| NRJ Howlett | John Street |

| Eric Beare | Albert J White |

Figure 20. Memorial in Egloshayle to ten parishioners who died in the Second World War.

In this very small sample, some of the common iconography from the Great War windows was still being used after . At Egloshayle, , a communal window for ten parishioners who died in the war repeats the images of Saints Michael and George (Figure 20). Similarly, at Lelant, , a kneeling soldier before Christ receives a crown from an angel in a communal window for ten named parishioners. Interestingly the tracery contains two images of sacrificial iconography, namely the Agnus Dei, but also the much rarer Pelican in her Piety, a common image up to the end of the nineteenth century but rarely used in the twentieth.

Three post- memorial windows deserve closer study for the ways in which the iconography of remembrance is extended:

Millbrook

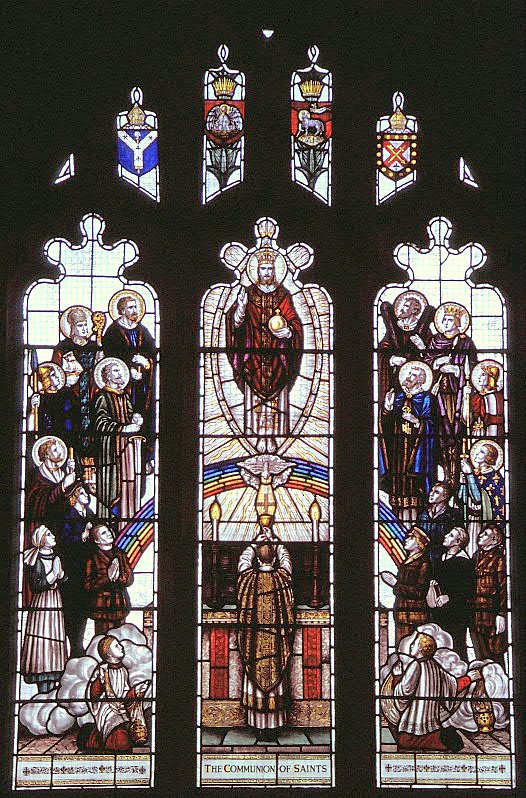

The Communion of Saints.

Figure 21. Memorial in All Saints, Millbrook showing Christ in Majesty in a Te Deum setting. The arms in the tracery on the left-hand side are of the Archdiocese of Canterbury and, on the right-hand side, the Diocese of Truro.

Millbrook has a communal window, , showing a typical Christ in Majesty in a Te Deum setting. Amongst the groups of service personnel (male and female), however, are members of the civilian services for the first time (Figure 21). Also the tracery, besides the arms of the Canterbury and Truro sees, also contains the Agnus Dei and the Pelican in her Piety again.

St Stephen-in-Brannel

Figure 22. Detail from the memorial window at St Stephen-in-Brannel, showing a potter working in his studio.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

Figure 23. Detail from the memorial window at St Stephen-in-Brannel, showing a housewife preparing a meal in a contemporary (s) kitchen.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

St Stephen-in-Brannel has a most remarkable communal window, , that really pushed traditional iconography farther than anything up to this time. The central lights of this four-light window are dominated by a Last Supper with the Agnus Dei below, together with the Peacock, symbols of sacrifice and resurrection. The outer panels contain four images of local industry, whose themes link back to the events of the Last Supper. To the left are scenes of the china clay extractive sites, whilst to the right are scenes of crop farming. The final panels at the bottom both contain images of the return to normality after warfare. The potter is working in his studio whilst the housewife is preparing a meal in a modern (s) kitchen (Figures 22 and 23). Like the earlier post- window at St Stephen-by-Launceston, there is a reflective element in this window that makes it stand out from the normal war memorial windows of its time.

St Eval

Per ardua ad astra (Through adversity to the stars).

De profundis clamavi (Out of the depths have I cried [unto thee, O Lord]) ().

Figure 24. Memorial at St Eval to the servicemen of Coastal Command. At the bottom left is the badge and motto (Constant Endeavour) of RAF Coastal Command and at the bottom right is the badge and motto (Faith in our Task) of RAF St Eval, which incorporates a picture of the church.

High-resolution image will start to load shortly …

St Eval’s memorial, , to the Coastal Command servicemen who lost their lives in the Second World War is the most powerful of all Cornish war memorial windows, using a totally different artistic style and iconography. The badges of RAF Coastal Command and RAF St Eval are included together with the RAF motto Per ardua ad astra (Figure 24). The main image is of a red crown of thorns for sacrifice, surmounted by the Alpha and Omega, and the five wounds of Christ as red dots at the head of each light. In the tracery, stars gleam in a dark night over the Atlantic (a wondrous use of varied blue antique glass). Beneath the crown is the suggestion of a gigantic wave with the inscription from Psalm 130—De profundis clamavi (Out of the depths have I cried [unto thee, O Lord]). It is fitting that this, hopefully, final war memorial window in Cornwall should be such a deeply artistic and moving contribution on the price of war in human suffering.

Conclusion: remembering loss, suffering and sacrifice.

To the memory of Captain PERCY ASHTON, M.C., who served with the 1st. & 8th. Battns. D.C.L.I. in France & Salonika – and died from the effects of War Service .

A man courageous courteous kind

Through suffering of steadfast mind

Figure 25. Memorial at St Petroc, Bodmin.

To bring this survey of Cornish war memorial stained glass windows to a close,

we return to St Petroc, Bodmin, where a late First World War window,

,

was inserted in .

The tracery shows the crucifixion with Mary and John. The main images are from the legends of Arthur and Percival,

and the English Christian kings Richard and Edward .

Thus once again the chivalric sacrifice from the legends of the Round Table and medieval times is

linked to the waging of just wars. The inscription for one of the dedicatees, Captain Percy Ashton,

highlights the suffering that results from all wars:

who served with the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry in France and Salonika,

–,

and who died from the effects of War Service,

(sixteen years after the end of hostilities):

A man courageous, courteous, kind, Through suffering of steadfast mind

(Figure 25).

The other dedicatee is Maj Gen Sir John Inglis who commanded the garrison

at the siege of Lucknow in , which takes us neatly back

to the first Cornish war memorial window at Kilkhampton.

We have seen that the particular nature of war memorial windows in a sacred setting, whether they commemorate an individual or group, produced a range of iconography that separates such windows from all other church memorial windows and secular war monuments. Some iconographical themes remain constant over one hundred and fifty years, particularly the emphasis on suffering, sacrifice (Crucifixion) and the certainty of resurrection (Christ in Majesty, and archangels) and the triumph of good over evil (Michael and George). Patronal (often Cornish) saints and Cornish images reinforce the geographic location of these windows.

On the other hand, some iconographic themes evolved as society and culture values changed over time. Personalising the dedicatee by the use of photographic images came and went. The imperialist overtones of the pre- windows, together with the ‘safe return’ dedications vanished with the horror of the Great War. The images of medieval chivalry and sacrifice hardly bore comparison with the brutal mechanised killing of –. Gradually, the subjects of some windows turned to the prospect of peace after warfare, and the return to civilised normality and a better future.

The common feature of so many of these windows is the overwhelming sense of grief

and the loss of young lives, and this again marks the difference between ordinary memorial windows

and war memorial windows. In the former, the usual donors are the children and the dedicatees are the parents.

In war memorial windows, the reverse is true—parents are grieving for

children30.

If sometimes the iconography of war memorial windows can seem repetitive,

one must remember that the sense of remembrance was particularly raw to the members of the

donor family, and the windows were not only an act of remembrance of the dedicatee

but also one of consolation for the donors. Thus both Saints Michael and George portray

Evil defeated by Good. In addition, Michael (and Resurrection themes) promised a life after death,

whilst George’s role as patron saint of England endorsed personal sacrifice

in the cause of a just war

.

Looking at the one hundred and fifty years of imagery in these windows one can see a conflict between remembrance of personal loss and the advocacy of the sentiments behind the phrase pro patria mori:

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori

(It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country) (Horace Odes). This tension is perhaps shown by quoting two excerpts of poetry:-

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.31

Quite rightly, these lines are absolutely central to all acts of remembrance today. What are often overlooked are the sentiments of the preceding lines of the poem:-

They went with songs to the battle, they were young.

Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

Such lines seem irreconcilable with those of Wilfred Owen:-

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Ultimately, these contrasting responses to the subject of war and its effects must be irreconcilable. As we have seen, these tensions are in the Cornish war memorial windows and they are shown in the contrast between typical war memorials with a grieving soldier with reversed arms compared with the s triumphal memorial in Truro’s Boscawen Street. What is undeniable even today is the emotional impact of such memorials and acts of remembrance. A final, telling image (Figure 26) is that of ten thousand poppies (one for each Cornish serviceman killed or missing in the Great War) falling from the crossing in Truro cathedral at the .

Figure 26. Ten thousand poppies falling from the crossing in Truro Cathedral at the .

References

- JH Markland, Remarks on English churches, and on the Expediency of Rendering Sepulchral Memorials Subservient to Pious and Christian uses. Oxford, .

- Revd John Armstrong, Transactions of the Exeter Architectural Society. .

-

There are only two major articles on Victorian memorial windows:

- Michael Kerney, The Victorian Memorial Window, Journal of Stained Glass, Vol (), pp 66–93. British Society of Master Glass Painters.

- Michael G Swift, Piety, Power and Pride, .

- RM Paul, Truro Diocesan Magazine , , p 110.

-

The usual wording on French war memorials is

Aux enfants de … morts pour la patrie.

. - Lawrence Binyon, For the Fallen.

- Wilfred Owen, Dulce et decorum est.