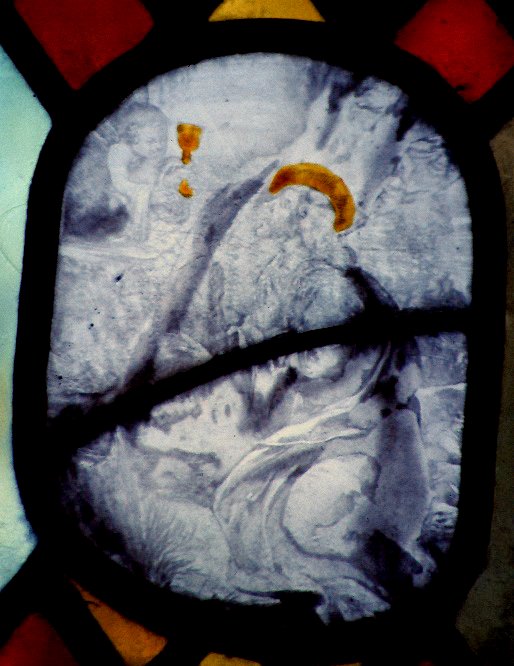

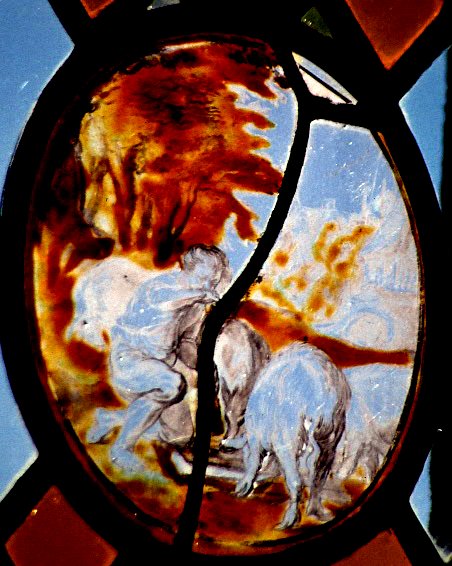

16th and 17th century stained glass roundels in Pendeen church, Cornwall

A version of this article was published in the CVMA magazine Vidimus vol. 36, February 2010.

The small Cornish village of Pendeen abuts rugged Atlantic coastland three miles east of St Just. The parish church contains a barely known collection of pre-1700 continental glass panels assembled by one of the foremost preachers of Victorian England, the Revd Robert Aitken (1800–1873). The glass collection is not described in William Cole’s Catalogue of Netherlandish and North European Roundels in Britain, Corpus Vitrearum Great Britain, Summary Catalogue 1, Oxford, 1993 and nor was it mentioned in the earlier editions of Nikolaus Pevsner’s volume on Cornwall in the Buildings of England series (since corrected in the 2014 edition).

Until 1843 the modern parish of Pendeen was part of the mother parish of St Just-in-Penwith. Following the New Parishes Act of that year, however, which created independent parishes from larger districts (known as ‘Peel Districts’ after the prime minister who promoted the act: Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850)) the community was separated from St Just and encouraged to go its own way. In the event, it struggled for three years without either a church or a parish priest, until Bishop Henry Phillpotts (1778–1869) of Exeter offered the post to the Revd Robert Aitken (Figure 1)

Aitken was in his fiftieth year and had already had a colourful career in the church. He had been ordained in 1823 but,

after a dispute with the Bishop of Chester, he moved to the Isle of Man where he was a regular preacher on the Methodist circuit.

He subsequently returned to the Church of England and became known throughout England as an evangelist of almost unrivalled fervour.

One who heard him described the experience thus: I thought I could distinguish very perceptibly an effort in the preacher to

produce an animal excitement … I could not divest my mind of the idea of a maniac

. Aitken had his largest following in Liverpool

where his supporters attracted attention mainly because of their frenzied revivalist activities in the vaults of Hope Hall;

it was standard practice for members of the congregation to rise up, dance and caper about the room, jump over the forms,

tear their hair and clothes, and throw themselves on the floor. Apart his work in Liverpool, he also held positions

in deprived urban parishes in Leeds and London, before becoming curate of Perranuthnoe near Marazion in Cornwall.

His response to the Bishop’s invitation to become the incumbent of the parish of Pendeen in 1849 did not get off to a good start. He got lost in fog and, finding nothing but moorland with no church or school, he returned home. However, a local petition resulted in more pressure on Aitken by the Bishop, and a second visit secured his acceptance of the position. A temporary wooden church was replaced after two years by the present church of St John the Baptist, which was opened on 1st November 1851. It was built to Aitken’s own designs and by local craftsmen under his personal supervision. According to William Lake’s Parochial History of Cornwall, it was modelled on the ancient cathedral of Iona. The site was later enlarged with schools and a rectory, the whole group of buildings being tied together by a series of high-walled enclosures with battlemented gateways and ornamental gates, all to Aitken’s designs (Figure 2).

Aitken was a tireless preacher who was regularly in demand to speak at missions throughout the industrialised urban centres in the country. His creed was a combination of evangelism, stemming from his Methodist experiences of the process of ‘conversion’, and the sacramental beliefs of high-church Anglicanism, known as Tractarianism. Whilst he was curate at St James, York Square, Leeds (1840–43) it became the only Leeds church to have a weekly early-morning communion, and he also established a quasi-monastic community there. Disputes over the place of such an ‘Evangelical-Tractarian’ within the established church lasted until well after his death.

In accordance with his Tractarian wish to enhance the celebration of the sacraments in his new church, Aitken was determined

to enrich the building with stained glass. Unfortunately, the building had exhausted the capital fund of £2,000, and was in deficit.

Whilst the coloured glass of the Chancel east window was funded by the local Ladies’ Guild Association, the remaining windows

would have remained as plain glass had Aitken himself not donated a series of twelve roundels that he had collected from antique shops in London.

These were set in execrable crudely-coloured glass in six of the windows. When complete the

described them as All the windows are of coloured glass, with painted centres,

many of which are of a very early date, and are curious on account of their antiquity

(Figure 3).

Unfortunately no records have been found of where Aitken bought his pre-1700 glass or how his gift was received by his parishioners.

Once the windows were completed, Aitken remained at the church until his sudden death on the Great Western Railway platform at Paddington on 11th July 1873.

Overall the glass is of mixed quality. Some seems to have suffered significant enamel paint loss, perhaps due to its proximity to the salt-laden air. Other panels have been broken and replaced. In 2001 a fine image of the Adoration of the Magi was shattered by vandals. Notwithstanding such setbacks the collection remains interesting and important, not just as previously unrecorded continental glass in England, but for the light it shows on how such glass was perceived by a passionate clergyman of the period. Rather than being arranged for any narrative or didactic function, it seems to have been used for its ability to enhance the definition of a church as a place of worship and beauty.

The Windows.

Aitken’s glass was set into six windows. Using the CVMA numbering system which works from east to west they are:

Further reading

- Obituary of Robert Aitken in the Guardian 23rd July 1873.

- .

- M.G. Swift An examination of the development of stained glass windows in the Anglican Churches of Leeds: 1841–1860. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Leeds, 1999.

- Charlotte E Woods. Memoirs and letters of Canon Hay Aitken with an introductory memoir of his father, the Rev Robert Aitken of Pendeen, 1928.