The stained glass windows of St Carantoc, Cornwall

A version of this paper under the title A Victorian vision re-discovered

appeared in the

Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, , pp 25–41.

Abstract

The restoration of St Carantoc parish church by Father George Metford Parsons was one of the most ambitious Anglo-Catholic restorations in late Victorian Cornwall. This paper places Fr Parsons’ scheme for the stained glass windows within the architectural and liturgical context of the church, and also examines the relationships between his scheme and that of Bishop Benson for the windows of his new Truro Cathedral.

The restoration of Crantock Parish Church

The principal beauty is its very rich High Church fittings, dating mainly from –. They include a splendid screen with coving, loft and rood, which incorporates a few medieval parts. There are fine parclose screens, rich sanctuary panelling, reredos, timber sedilia, and lavish stalls including four modern misericords. The pews have good carved ends in the late medieval manner. The largely renewed roofs have fine colouring above the rood and the sanctuary.1

This authoritative summary of the late-Victorian restoration of St Carantoc has one astounding omission: it contains no reference to the fifteen new stained glass windows that were an integral part of the restored church. When the church was re-opened in by the Bishop of Truro the Rt Revd John Gott, after a two and a half year closure, ten of the windows had been inserted, and the glazing was completed, together with many other internal fixtures and fittings, within the next three years.2

It was very rare for such a large number of stained glass windows to be inserted so rapidly in Cornish restorations. Crantock’s new windows were unique among parish churches of Cornwall in two crucial respects: all of the windows were part of a complete didactic scheme compiled by the vicar, and all were designed and executed by one stained glass artist.3 The pivotal role of the stained glass windows in this restoration can now been told for the first time.

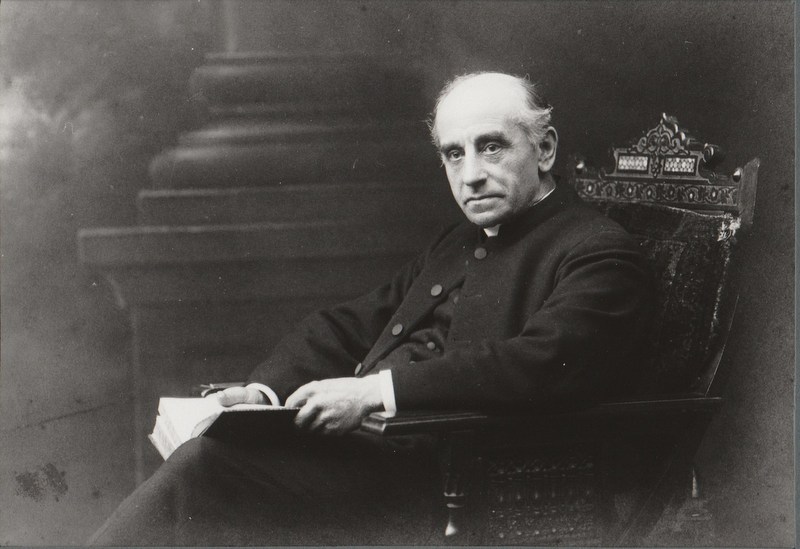

The Vicar

Father George Metford Parsons

After ten years as priest at the Church of the Holy Nativity at Knowle, Bristol, Fr George Metford Parsons

(–)

arrived at Crantock in . There he found a parish church with a venerable history reduced to

something near to a mere picturesque ruin

4

and with a very small congregation. Such was the drive and determination of Father George (as he was known locally)

that within eight years the Vicarage House, glebe barn and cattle house, as well as the church, were all restored

or completely rebuilt. Father George possessed enormous energy to achieve such results in so short a space of time,

as well as abundant fundraising skills.

Fr George (something of a hero

5

made no concessions in his High Anglican beliefs, insisting upon wearing his soutane and biretta

at all times.6 In this he was part of the tradition

of Anglo-Catholic priests that flourished in the new Diocese of Truro after .

Gradually, the parish accepted

Father George and his ritual, and the congregation grew as the restoration progressed.

The resulting set of stained glass windows reveals another indication of his Anglo-Catholic resolve. Rather than seeking donors for the windows and then leaving the choice of the subject-matter to them, which was the normal practice in Victorian restorations, Fr George himself drew up the detailed scheme for the windows,7 to which the donors readily subscribed.

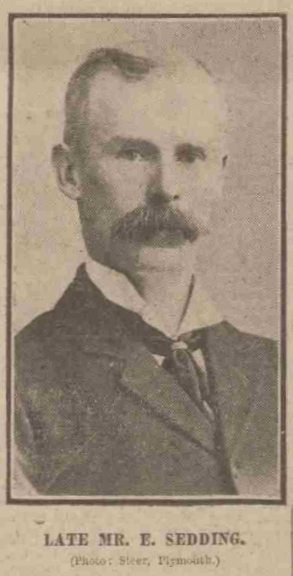

The architect.

Edmund Harold Sedding. (Photo: Steer, Plymouth.)

From www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Image © Local World Limited/Trinity Mirror. Image created courtesy of THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD.

The initial inspection of the church’s fabric was made in

by the distinguished London

architect GF Bodley.8

The architect entrusted with the actual restoration was Edmund Harold Sedding

(–),

son of the architect Edmund Sedding of Penzance. Both Edmund Sedding

(–)

and his younger brother John Dando Sedding

(–) had been trained in GE Street’s

architectural office.9

EH Sedding opened his practice in Plymouth in ,

and soon established a reputation throughout

the Diocese of Truro for his sympathetic church restorations and his informed knowledge of medieval

Cornish ecclesiological architecture.10

A High Anglican like his father and uncle,11

he took as his main principle the Tractarian concern to so order the worship in an Anglican Church

and its surroundings as to proclaim the Catholicity of Anglicanism and its fitness to stand alongside

the great churches of Christendom as an equal partner,

sharing apostolic faith and order.

12

Father George’s scheme for the stained glass windows was the most obvious expression of this aim,

being a robust Anglo-Catholic response to the challenges of both the Low Anglican Church and

the Nonconformists.13

Sedding was involved with over twenty further Cornish church restorations,14

but only in his restoration of Lanteglos-by-Fowey was a set of windows immediately inserted by a single studio,

but there is no evidence of a predetermined scheme.15

The stained glass designer

The artist and designer chosen for Crantock’s windows was Charles Edward Tute (–). Tute gained his initial experience in the prestigious and popular studio of Charles Eamer Kempe (–), and Kempe’s artistic style remained a feature of his window designs for the rest of his career. His designs were in regular demand16 throughout the country for a couple of decades before he emigrated to Australia in 1906. For much of his career in England, Tute worked from Gray’s Inn Road in London. The Crantock windows were made by Messrs EC O’Neill of the same London address as Tute.17

Stained glass didactic schemes

Such schemes were a common feature of ecclesiastical window glazing from medieval times onwards to the present day. Medieval schemes have survived in their entirety in great High-Gothic cathedrals such as the 13th century glass of Chartres18 and Bourges19 in France, to the 16th century schemes at King’s College Chapel, Cambridge20 and parish churches such as Fairford in Gloucestershire.21

Whatever their age and scale, all such integrated schemes had certain features in common. Firstly they presented multi-layered theological ideas, religious narratives and personages in a coherent and logical sequence. Secondly, such glazing schemes utilized the features of the building’s architectural space, and related the iconography of the windows to the functions of liturgy and worship within that space. Thirdly, the glazing schemes had an overall artistic unity and design. Lastly, these decorative artistic schemes had a didactic purpose, in that besides enhancing the worshipful atmosphere they were also intended to teach and instruct.

Cornish stained glass didactic schemes

The only Cornish precedent for such a scheme was the windows at JL Pearson’s new cathedral at Truro. This monumental scheme for over seventy window designs was originally designed by Bishop Edward White Benson in 1879 and published in full at the cathedral’s consecration in 1887:

In many of our older Cathedrals … the windows are often disfigured, not only by inferior glass, but incongruous subjects; while in other cases, where the material and execution are good, there is a total lack of sequence of thought, and an absence of clear and definite meaning in the glass that has, perhaps, cost very large sums of money.22

When Truro’s master scheme was published, it stressed the need for artistic unity as well as theological coherence and liturgical relevance. To ensure such artistic unity, the commission for the entire set of the new cathedral’s windows was awarded to the prestigious London studio of Clayton and Bell. When Crantock’s restoration commenced, Truro cathedral was already over a decade old and more than thirty of its windows had been inserted.23 As will be shown there are striking parallels between the intentions and content of both window schemes.

Following the example of Truro Cathedral, only three Cornish churches were to aspire to a complete scheme for stained glass windows. A short-lived example was the ‘iron’ mission church at Draynes, into which nine stained glass windows of female saints were inserted at its opening in 1888. These were made by Fouracre & Watson of Plymouth, and a contemporary report stresses the High Church intentions that lay behind such the installation of such a scheme for a mission church set in a mining area:

Putting away all prejudice about superstition and all unworthy fears of priestcraft in the bad sense of the word, we believe that the clergy generally would do well to make their churches and services warm and bright with colour. Poor people love it. It lifts them out of unlovely surroundings, helps them in reverence, and it seems to us that abuses are no more likely to creep in there than in the awful formality and deadness of many low and slow churches.24

Following the restoration scheme at Crantock, the nearby church of St Michael Newquay published a projected integrated scheme in 1914. The first three windows were inserted, but the project failed to be restarted after the First World War.25

The stained glass windows

Crantock church’s very unusual architectural layout, with a three aisled chancel, north and south transepts, and a single aisled nave, reflects its origins as a medieval Collegiate Church.26

St Carantoc, Crantock, Cornwall.

The chancel is loftier and on a larger scale than the nave, giving curious proportions to the building.27 Over half of the windows are located within the chancel and transept area. As with Truro cathedral, the basic ground form of the building is a cruciform shape, presenting the opportunity to use the ‘four great windows’ at the extremities of the east, south, west and north arms to portray themes of major theological significance. In addition, the iconography of Crantock’s chancel windows relates directly to their sacramental liturgical function, whilst the nave windows have references to the local parish.

The four great windows

Window 12: North Transept

Window 12, central light. The Fall. Whilst Eve presents Adam with an apple, the crowned serpent lies coiled in the Tree of Knowledge. Adam and Eve both hold lilies (Eve’s are pointing downwards).

This three-light window depicts three scenes of the Fall. Incidentally, the 1887 Truro Cathedral scheme also started with a sequence depicting the Fall in the lancets directly beneath the Western Creation rose window.

The right-hand light shows God’s Benediction of Adam and Eve; with the inscription in Latin.28 The central light shows Adam and Eve’s temptation.29 Whilst Eve presents Adam with an apple, the crowned serpent lies coiled in the Tree of Knowledge. Adam and Eve both hold lilies (Eve’s are pointing downwards), the lily being one of the later emblems of the Blessed Virgin Mary who is the subject of six subsequent windows. The left-hand light shows the Expulsion from the Garden, a clothed Adam and Eve cover their eyes, whilst the angel behind them brandishes a flaming sword. The inscription30 provides a direct link to the next window in the sequence and the Incarnation. One major oddity in this window is that it reads from right to left, contrary to the accepted practice for narrative windows to read from left to right. The only explanation is that by adopting a ‘right-to-left’ layout, the viewer is then directed westwards towards the next window in the sequence, the Tower west.

Window 9: Tower west

Window 9, left-hand light. The Incarnation. A shepherd and a kneeling angel.

The second of the ‘great windows’ is a depiction of the Incarnation. This is a continuous scene across all three lights, with the Holy Family in the centre.31 The infant Jesus, the ‘Second Adam’, is the focus for the whole window, with Mary seated and Joseph standing. To the right are two generations of Shepherds, with the ox and ass in the background. To the left are a further older shepherd and a kneeling angel. This angel shows Tute’s indebtedness to the artistic style of CE Kempe, in its richly golden-stained garment with contrasting black, and magnificent peacock wings.

The recommended route now moves back to the crossing, but in doing so, the viewer should pause at the

rood screen.32

Although this is not technically part of the stained glass scheme, contemporary documents

place the rood screen together with the four great windows as an integral scheme to illustrate

the five principal Mysteries of Human Redemption.

33

The Crucifixion links chronologically the Incarnation in the Tower window to the South Transept Resurrection scenes.

Window 6: South Transept

Window 6, left-hand light. Quod vidimus annuntiamus vobis (That which we have seen declare we unto you) (1 John 1:3).

St John kneels in front of the empty tomb whilst St Peter stands behind him.

This three-light window depicts three post-Resurrection scenes. In the left light St John kneels in front

of the empty tomb whilst St Peter stands behind him.34

In the right-hand light, Mary Magdalene, carrying a jar of ointment, is confronted by the

guarding angel.35

The central light according to the Parsons scheme depicts the Risen Lord and the B.V. Mary

,

but the image reflects the standard

Noli me tangere36—the appearance

of the risen Christ to Mary Magdalene in the garden, and shows this moment of recognition to the first Christian witness.

The recommended route for the last part of the scheme proceeds through the screen to the communion rail in front of the chancel altar.

Pasce oves meas (Feed my sheep). D(omi)ne tu scis quia amo te (Lord thou knowest that I love thee) ()

. Christ, with stigmata on his hands and feet, is depicted as a shepherd leading two sheep. Peter kneels on the shore with his fishing boat in the background, and beside him are crossed keys.

This window is not part of the ‘four great windows’, yet it has a place in the overall didactic scheme. It is a simple two-light scene showing Christ’s charge to Peter.

Although this window is not part of the basic sequence it is sited in a liturgically significant position by the church’s sanctuary rail. The window represents the beginning of the History of the Christian Church, and significantly emphasises the principle of Apostolic Succession stretching right back to the authority of Christ’s commission to Peter, the first Bishop of Rome.

. In the central light, a crowned Christ holding the orb is enthroned in Glory. Below him, the Blessed Virgin Mary is also crowned. There are fifty-two other people in the window. Christ is surrounded by ranks of crowned seated figures as the Company of Heaven. At Christ’s feet are the emblems of the four evangelists: Matthew (angel); Mark (winged lion); Luke (winged bull); John (eagle). In the foreground and in the first and fifth lights are the company of saints, female to the left and male to the right. Many are recognisable by their attributes: Catherine (wheel), Clare (crozier), Catherine of Siena (lily), Mary Magdalene, John, Peter (keys), Paul (sword), Stephen (stones), Gregory (dove) and John the Baptist (lamb).40

The climax of the schemes for the four great windows at both Truro cathedral and Crantock set in the dominant position in the sanctuary above the main altar is a Te Deum portrayal of Christ in Glory surrounded by all the company of Heaven. The tracery of Crantock’s five light window contains the nine orders of angels, Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones; Dominations, Virtues, Powers; Princedoms, Archangels, Angels. In this tracery, only Archangels (St Michael), Thrones, Seraphim and Cherubim are differentiated. Beneath, the Blessed Virgin Mary is also crowned, another example of Anglo-Catholic iconography. Significantly, this window directly faces the Nativity scene in the Tower west window.

Truro cathedral’s scheme for its four great windows places the Holy Trinity in each of the three rose windows, followed by Christ in Glory, a journey from the beginning to the end of time. At Crantock the journey starts with the first Adam and the Fall; then the Incarnation, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, and finally Christ in Glory. Both schemes utilise the symbolism of the cross in the cruciform shape of the building to focus on its theme of Christ as the Son of God.

The Lady Chapel windows

The second part of the scheme concerns the three windows for the Lady Chapel. Here the subject-matter is totally concerned with Marian iconography, far more than is usual in Anglican parish churches. These images are supplemented by the roof bosses, which are Types for the Incarnation and the Blessed Virgin Mary.41 All of this emphasises Father George’s Anglo-Catholic intentions to portray the role traditionally given to her by the Church as one predestined to bring about the redemption of man from the ‘sin of Eve’.42 This sequence of the Marian windows is designed to be read from west to east, starting from the rood screen to the east window behind the altar, where this final image of the Madonna and Child in the centre of the east window forms the dominant visual focus for the whole architectural space.

Window 5: Lady Chapel south 2

Window 5 central light. Sic in sion firmata sum (So was I established in Sion) (Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach [Ecclesiasticus] 24:10).

Mary as a young girl being instructed to read by her mother Anne, and holding a scroll on which is written Et egredietur virga de radice Iesse et flos de radice eius ascendet (And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots) (Isaiah 11:1).

This three-light window contains early episodes in the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary taken from

the medieval source-text The Golden Legend. The right hand light shows the infant Mary

in the arms of her father Joachim, whilst her aged mother Anne is seated over an

empty baby’s crib.43

The homely domestic setting avoids any confusion with that of the Nativity at Bethlehem.

The central light was a common image in medieval iconography, namely Mary as a young girl

being instructed to read by her mother Anne.44

The left hand light45

shows Mary as a young woman reading a scroll text, with angels in the background behind her.

The Golden Legend maintained that Mary was brought up as a child in the temple at Jerusalem with other virgins,

and was visited daily of angels.

46

The scroll that she is reading says behold a virgin shall conceive

.47

In me sunt Deus vota tua (Thy vows are upon me O God) ()

c. The marriage of Joseph and Mary. A High Priest stands between them and at their feet are two doves.

The second window in this sequence draws on sources from both the Golden Legend and the early part of the Gospel narrative. The right hand light shows the rare subject in windows of the marriage of Joseph and Mary. Joseph is as usual portrayed as an older man and a High Priest stands between them. At their feet are two doves, one referring to the traditional dove that appeared on Joseph’s staff when he was chosen as Mary’s suitor,49 and the other prefiguring its appearance in the central light which shows the Annunciation to Mary. The Archangel Gabriel stands behind Mary, who is kneeling at her prayer-desk. Prominently in the top of the light is the descending Dove of the Holy Spirit. The scrolls of the inscription50 twine around Mary’s Lily emblem, the emblem of Purity. The left hand light shows the Visitation: the meeting of mutual rejoicing between Mary and her cousin Elizabeth.51 Elizabeth was in the sixth month of her pregnancy (John the Baptist).

Benedicta tu inter mulieres mater d(omi)ni mei (Blessed art thou among women … Mother of my Lord) ()

The tracery for this window52 contains panels showing the Archangel Gabriel with two attendant angels, a direct reference to the preceding scene of the Annunciation. Mary is the main figure in the central light, holding the infant Jesus. To her left kneels St John the Evangelist, a reference to the Crucifixion narrative where John was entrusted with the care of Mary.54 John is holding a palm, not a martyr’s palm, but the specific one belonging to the Virgin and traditionally handed on to him on her death.55 To her right, the other kneeling figure is St Joseph, also holding a palm.56

The Nave windows

St Carantoc’s nave is one of its strangest architectural features, being very narrow compared

to the three-aisled choir57.

In medieval times the members of the collegiate church had the sole use of the choir area.

Also, there is a distinct slope towards the west end: The little nave was so constructed to follow the slope of the hill,

whereas the chancel was built fairly level.

58

It is appropriate that the subject of the four windows of the nave for the use of the local medieval congregation

should be narratives from the life of their own patronal saint. The particular problem with the Celtic saints of Cornwall

is that there is little factual basis for the events of their lives, and St Carantoc is no exception.

The Lives of the Saints were not based on earlier historic records, but on local folklore

and contemporary views of what a saint should be like.

59

Our Knowledge of St Carantoc’s legend comes from two brief twelfth-century Latin Lives written in South Wales,

which attribute to him missionary activity in Ireland and south-west England,

including the founding of a church there.60

The nave windows of St Carantoc are a fascinating example of what Fr George thought a

pre-medieval saint should be like in a late Victorian didactic scheme!

In the following account, the windows have been arranged to be read in a chronological sequence.

Window 11: North Nave 1

Window 11. Obliviscere populum tuum et domum patris tui (Forget also thine own people, and thy father’s house) (Psalms 45:10).

The young St Carantoc, shown as a Celtic hermit preacher, lands on the north Cornish coast. Over his acolyte’s head hovers the Dove of the Holy Spirit. On the right are two local martial figures with their swords, spear and horned helmets.

In this two-light window, a very youthful St Carantoc is shown landing on a typical North Cornish coastline. He is portrayed as the typical image of a Celtic hermit preacher and the inscription61 enhances the spirit of the missionary in a pagan land. Over his acolyte’s head hovers the Dove of the Holy Spirit. His vulnerable appearance is a dramatic contrast to the two local martial figures, with their swords, spear and horned helmets.

Window 7: South Nave 1

Window 7. Domine deduc me in justitia tua (Lead me O Lord in thy righteousness) (Psalms 5:8). Dirige in conspectu tuo viam meam (Direct my way in your sight) (first words of the first antiphon in the Matins of the Office for the Dead, based on Psalms 5:8).

St Carantoc, in a coracle and portrayed as a deacon, follows the floating altar, complete with candles, chalice, paten and censer, up the Gannel. The altar has a guardian angel.

This is the only one of the four windows in the nave sequence which is founded on the medieval legend of St Carantoc. The window depicts the floating altar that St Carantoc followed up the Gannel, complete with candles, chalice, paten and censer; a robust statement of Anglo-Catholic ritual status! The altar has a guardian angel, and the saint is in a coracle following it.62 According to the legend, King Arthur had promised St Carantoc the site for his church wherever the altar landed.63 The portrayal of the saint has now progressed from a hermit preacher to that of a deacon.

Window 8: South Nave 2

Window 8. In nomine meo daemonia eiicient; linguis loquentur novis; serpentes tollent (In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; they shall take up serpents) (Mark 16:17–18).

St Carantoc, portrayed as a priest and holding a crucifix in his right hand, converts the local community at Tintagel. The local king is seated on a throne, flanked by two armed attendants, a woman and two children. The setting is a harbour with a Viking-style boat and a castle on the far shore.

St Carantoc’s narrative now proceeds to the conversion of the local community at Tintagel. The local king is shown seated on a throne, flanked by two armed attendants, a woman and two children. The setting is a harbour with a Viking-style boat and a castle on the far shore. St Carantoc is now portrayed as a priest with a crucifix in his right hand.64 The whole scene has echoes of the popular New Testament scene of Christ summoning little children unto him.

Window 10: North Nave 2

Window 10. Vos scitis quanta ego et fratres mei fecimus pro legibus et pro Sanctis (Ye yourselves know what great things I, and my brethren [and my father’s house] have done for the laws and the sanctuary) (1 Maccabees 13:3).

A priest (presumably St Carantoc) sits with a scroll, on which is written Seanghus Mor, on his knees, in front of a bishop (who could be St Patric) who is holding a blank scroll.

The final window in the St Carantoc narrative poses considerable interpretative problems to the modern viewer. On the one hand, it can be read as a representation of the legendary role played by St Carantoc in the harmonisation of Christianity with secular law in Ireland.65 The scene shows a seated priest with a written scroll on his knees, in front of a bishop who is holding a blank scroll. The priest’s scroll is inscribed Seanghus Mor, referring to the Senchas Mar, an early Irish compilation of law-texts written in the seventh and eighth centuries. Later Irish legend claimed that this text had been compiled by St Patrick in the fifth century, with the assistance of three kings, three bishops and three professors of secular learning, and that it had served to make secular Irish law compatible with Christian doctrine and ethics. The Irish legend named St Cairnech of Dulane (County Meath) as one of the three bishops who assisted St Patrick, but the twelfth-century Welsh Life of St Carantoc claimed that Cairnech was the Irish name of St Carantoc, who during his supposed visit to Ireland had therefore taken part in this major legendary event of early Irish history.66 The seated figure holding the scroll reading Seanghus Mor is therefore presumably St Carantoc, and the bishop holding the blank scroll could therefore be St Patrick. The Celtic tradition is represented by the Holy Well and Celtic cross, whilst the bard-like figure and the king in the background presumably represent other categories of Celtic society who assisted St Patrick.

One problem in this interpretation of the window, however, is that the priest’s face has obviously been painted from a photograph of an actual person. Such photographic images were common in late Victorian stained glass. The face has been identified as that of Revd RA Suckling (1842–1917),67 who succeeded the famous, some would say notorious, Revd Alexander Heriot Machonochie at St Alban’s Holborn in 1882,68 a church famous for its spirit of mission in the deprived areas of East London. EH Sedding’s uncle, John Dando Sedding, was churchwarden of St Alban’s Holborn for ten years until his death in 1891.69 In his later life, one of the founders of the Oxford Movement Edward Bouverie Pusey was a frequent summer visitor to Crantock, and his favourite chair is in the sanctuary. Suckling succeeded Pusey as warden of Ascot Priory’s Society of the Most Holy Trinity, the centre for the Community of the Sisters of Charity, the first community of Anglican nuns.70

There is thus an intended Tractarian sub-text to this window. Late Victorian High Churchmen like Father George and Bishop Benson were faced with what they believed was the problem of combining the tradition of ‘Celtic’ Christianity with that of the Apostolic Succession of the Church of Rome.71 It formed an important theme in Benson’s Church History sequence in his window scheme of Truro Cathedral.72 All this evidence supports a further reading of the scene in this Crantock window as one where the ‘Celtic’ tradition (represented by St Carantoc) and the Roman tradition (represented by St Patrick) were reconciled, and it is easy to see the appeal of such a theme to a Ritualist like Father George.

Some conclusions on the St Carantoc sequence

One of the main functions of integrated window schemes is to relate their iconography to the liturgy and architectural space. At Crantock the font is positioned between South Nave 2 and North Nave 2 windows. In the first, St Carantoc is shown converting the local population, a process that would involve immediate baptism; and in the second the transition from the Celtic to the Augustinian churches involved the adoption of Augustinian sacraments, notably, in this case, baptism. So, one result of Fr George’s scheme is to include a baptism theme as part of the sequence on the patronal saint.

Bishop Benson’s didactic scheme for the windows of his Truro Cathedral placed great emphasis on the theme of Christian mission, and mission in Cornwall in particular.73 When the cathedral was consecrated in 1887, the baptistry windows were already inserted, and these showed four Cornish Celtic saints: St Winnow as a preaching hermit, St Constantine as a converted Christian king, St Mabe as a priest, and St Paul Aurelian as a bishop.74 The parallels between these Truro windows and the ways in which St Carantoc are portrayed are sufficient to suggest that Father George had an intimate knowledge of the cathedral scheme and its baptistry windows that were already inserted.

It could be argued that the challenges facing the Celtic Saint were not dissimilar to those of the new vicar in 1894, and that part of the windows’ teaching purpose was to draw a parallel between the ancient pagan society in which the Saint found himself and Fr George’s experiences in the non-Conformist and secular society of his parish at the end of the nineteenth century.75

The North Chancel aisle windows

The three windows of the North Chancel aisle (the modern vestry) do not form a themed sequence in themselves, but they all share the same architectural space, and in their own ways fulfil teaching purposes.

Window 13: Vestry north 2

Window 13. Ego sum Raphael unus ex septem (I am Raphael, one of the seven [holy angels]) (Tobit 12:15).

The archangel Raphael, holding a fish in his right hand.

This three-light window is next to the Temptation window in the North Transept. It depicts three messengers of God, namely the Archangels Gabriel, Michael and Raphael. Michael76 is shown slaying the dragon. Raphael77 holds a fish in his right hand, this being a reference to the Renaissance painter Raphael’s portrayal of Tobias (shown holding a fish78) being presented by the archangel to the enthroned Virgin Mary and Child. Gabriel79 is shown holding the same flowering palm that is in the hands of St John in the Lady Chapel east window. The scroll round the palm has the inscription Ave Maria. Interestingly, at Truro cathedral the same three archangels (plus the Archangel Uriel) figure prominently as part of the Garden of Eden sequence beneath the western rose window, and beneath Christ in Glory in the centre of the Great Chancel east window at the opposite end of the cathedral. Again, it reinforces the view that in 1898 Father George knew and was influenced by Benson’s 1887 scheme for the new Truro Cathedral.

Window 14: Vestry north 1

The last two windows relate closely to the more intimate space of the sacristy rather than the public spaces of the rest of the building. This single-light window is dominated by a flowing inscribed scroll80—a reference to gathering up the fragments of loaves at the Feeding of the Five Thousand—set in a background of assorted ‘medley’ glass.81 Tute assembled an assortment of older glass, reputedly unearthed during the church’s restoration82 and some of which is medieval, including a sun-burst and the partial heads of a human and an animal. There is a didactic purpose behind this window, in that it acts as a cogent reminder of the loss of over 90% of the country’s medieval glass, particularly during the Reformation and Civil War periods.83 This loss of Crantock’s medieval heritage must have been a very important element in Father George’s vision for the church’s restoration.

Window 15: Vestry east

Window 15. Non vos me elegistis sed ego elegi vos (Ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you) (John 15:16). Tu es sacerdos in æternum (Thou art a priest for ever) (Hebrews 7:17).

Christ administers the sacrament with the help of two deacons.

The final three-light window in the east wall of the Vestry has the most personal resonance. It shows Christ at the point of administering the sacrament with the help of two deacons.84 Again, there is a tradition of Ritualistic Anglo-Catholic priests putting such iconography in the east window of their vestries at the turn of the nineteenth century.85 It would have been the final window to be seen by the priest before entering the sanctuary for the Eucharist service.

This also shows the close relationship between the overall window scheme and liturgy, as Christ’s commission to St Peter in the Chancel south window is directly opposite. Such juxtaposition emphasising the Apostolic Succession would have had a great resonance with an Anglo-Catholic such as Father George.